What is "information"?

Three notes on meaning, practical reason, and the role of "ressentiment" in the drive to systematize.

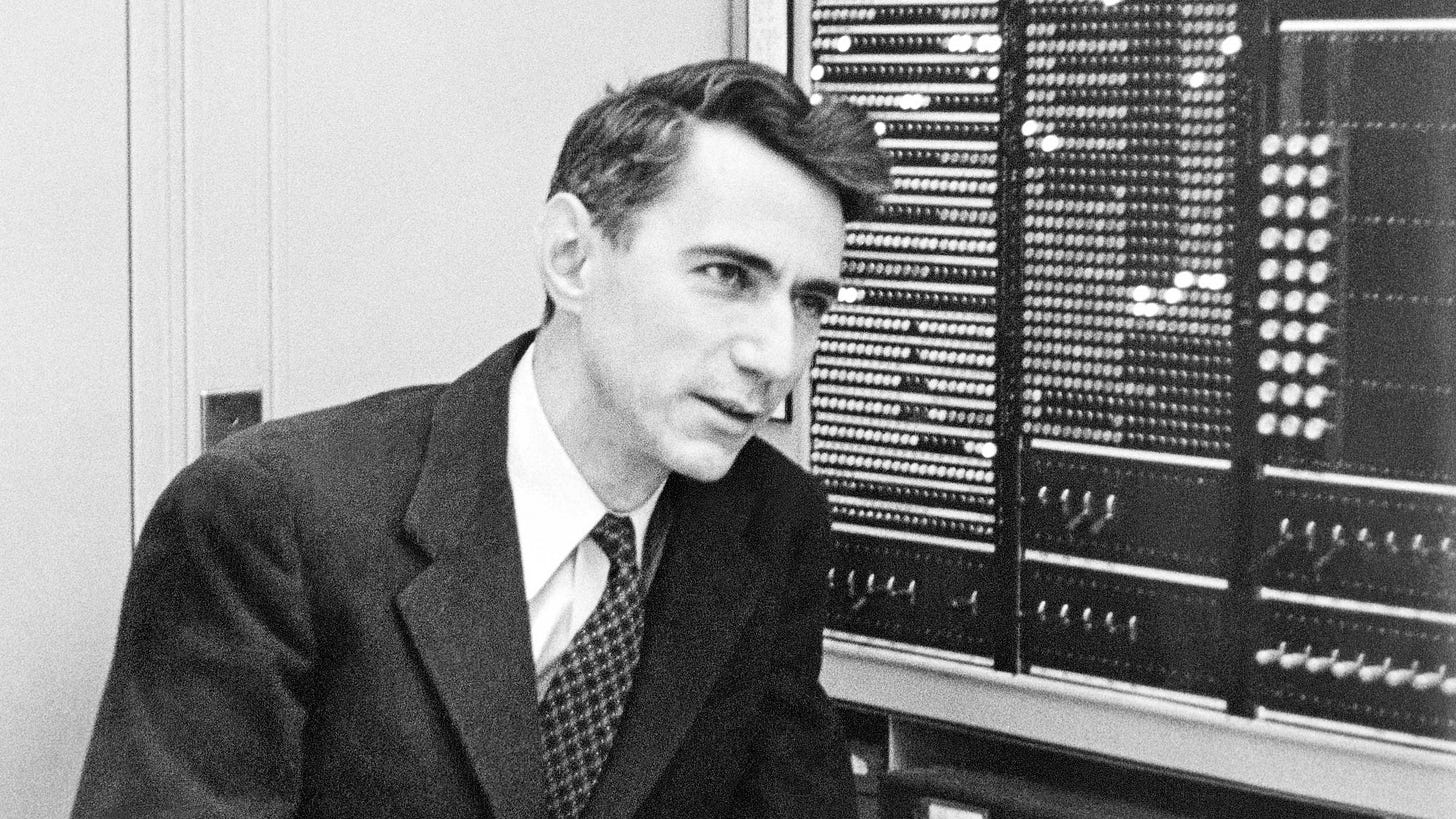

1. In the usage that was once most common, the word “information” denoted a report about the state of the world. It could also mean instructions for altering the world, for example, a recipe for beef stew. But in the 1940s, Claude Shannon of Bell Laboratories used it in a new way. His perspective was that of a mathematician who was trying to clarify some concepts that would be helpful to electrical engineers working for the telephone company. As used by Shannon, the word is no longer tied to the semantic content of utterances as grasped by sender and receiver; “information” in the new usage refers to the transmission of meaning rather than meaning itself, and it is quantitative, “a measure of the difficulty in transmitting the sequences produced by some information source”.1 In the new usage, “even gibberish might be ‘information’ if somebody cared to transmit it,” as Theodore Roszak writes.

Shannon’s appropriation of the common word “information” for this purpose has led to all manner of confusion, and infected our common use of the word in such a way that one must make an extra effort to preserve the idea of meaning, if that is what one intends. The net effect is to embolden what you might call abstraction-toward-the-generic, and to make this tendency seem somehow in harmony with technological progress. It becomes very easy to destroy meaning while believing that by “going meta” you are operating at a higher level. What this really amounts to is a leveling-down. To see this, let’s begin with one of the more eccentric points that Tocqueville made: the attractions of a false efficiency, in the domain of knowledge, express the spirit of democracy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Archedelia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.