The world upside down

Max Scheler on the moral inversion that grows out of resentment. Session 4 of the vitalism seminar.

Have you always had a fuzzy, background sense that we live in a sham world, in which up is said to be down and vice versa? If you sometimes suspect there is a fundamental mendacity in the valuations we officially assign to things and people, read on.

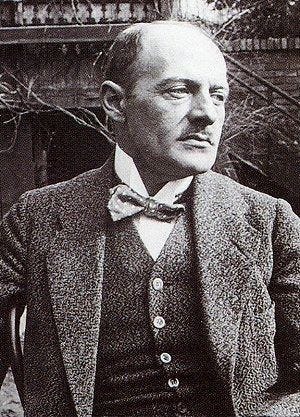

Max Scheler is the guy who can help us trace the roots of an epochal inversion of the meanings of good and bad, a development that reversed the evaluative outlook we catch glimpses of in fables and old histories. If that older outlook seems more solid and more real to you, yet somehow not permissible today, you have experienced the doubleness I refer to. The contemporary moral order feels like a translucent, sticky membrane laid over something hard and clear. Scheler opens the doors of perception for us by peeling the membrane away. He does so by elaborating Nietzsche’s concept of ressentiment, more fully than Nietzsche did himself. Scheler first published Ressentiment in 1912, with a revised edition coming out during the war in 1915.

It would be an easy matter to trace the operation of ressentiment through today’s various projects of egalitarian leveling: the collapse of standards of assessment; the cult of the victim; the hatred of beauty. In its more rarefied expressions, it shows up as hatred of the body as an impediment to autonomy (as in transhumanism), or as the “hermeneutic of suspicion” and “culture of critique” among intellectuals who can only tear down, never affirm.

Ressentiment is set of reflexes that build up around a hard nucleus: the denial of an objective order of good. Ressentiment is thus the psychological expression of nihilism. But the secret genius of ressentiment is that it has generated values of its own -- its own binding morality -- and in doing so turned the world upside down. The depth of this inversion of values is such that it would likely take centuries to overcome.

Among the scanty discoveries which have been made in recent times about the origin of moral judgments, Friedrich Nietzsche’s discovery that ressentiment can be the source of such value judgments is the most profound. This remains true even if his specific characterization of Christian love as the most delicate “flower of ressentiment” should turn out to be mistaken.

--Max Scheler, Ressentiment (1912)

The last bit in the quote above, about N being mistaken in his assessment of Christianity, will be the theme of next week’s installment. Today I am going to focus on Chapter One of Ressentiment and lay out the basic psychology of it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Archedelia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.